The Next Big Ones: what will the future pandemics be like?

In the last twenty years, three coronaviruses have managed to make the leap in human species and spread globally: SARS-Cov in 2003, MERS-Cov in 2012 and SARS-Cov-2 in 2019.

They were not the first and probably will not be the last ones. In fact, while the world is still grappling with this pandemic, someone is already thinking about what could be next, “The Next Big One”, as the science writer David Quammer wrote it in his book “Spillover”. Researchers have already identified numerous viruses with a high potential to become zoonotic, that is, to infect other animal species and humans.

THE TIP OF THE ICEBERG

The viruses responsible for SARS and COVID-19 would be just the tip of the iceberg. A study, published in pre-print, estimated that an average of 400,000 people are infected with coronaviruses from the same family each year. However, most of these phenomena do not give rise to a pandemic. The virus, in fact, must not only learn to open the "lock" of human cells, but must also be transmitted from one individual to another - and this, fortunately, is much less frequent. But just take a look at the numbers to realize that the COVID-19 pandemic was an accident. The probability that a global epidemic with these exact characteristics would occur was quite high (so much so that someone, ten years ago, had even predicted it!).

THE RISK FACTORS

In nature there are 1.7 million viruses still undiscovered in the animal world and at least half, 850,000, could be transferred to humans. In fact, it is estimated that 60% of all infectious diseases are related to contact with animals. Intensive farming, deforestation, illegal animal trade and global warming have altered the natural environment, bringing wildlife, viruses and humans closer together. We have lost almost half of our planet's forests, which have gone from 6 trillion to 3 trillion. Illegal trafficking of animals in Europe increased by 7%. Globally, the value of this trade fluctuates between 10 and 23 billion dollars a year.

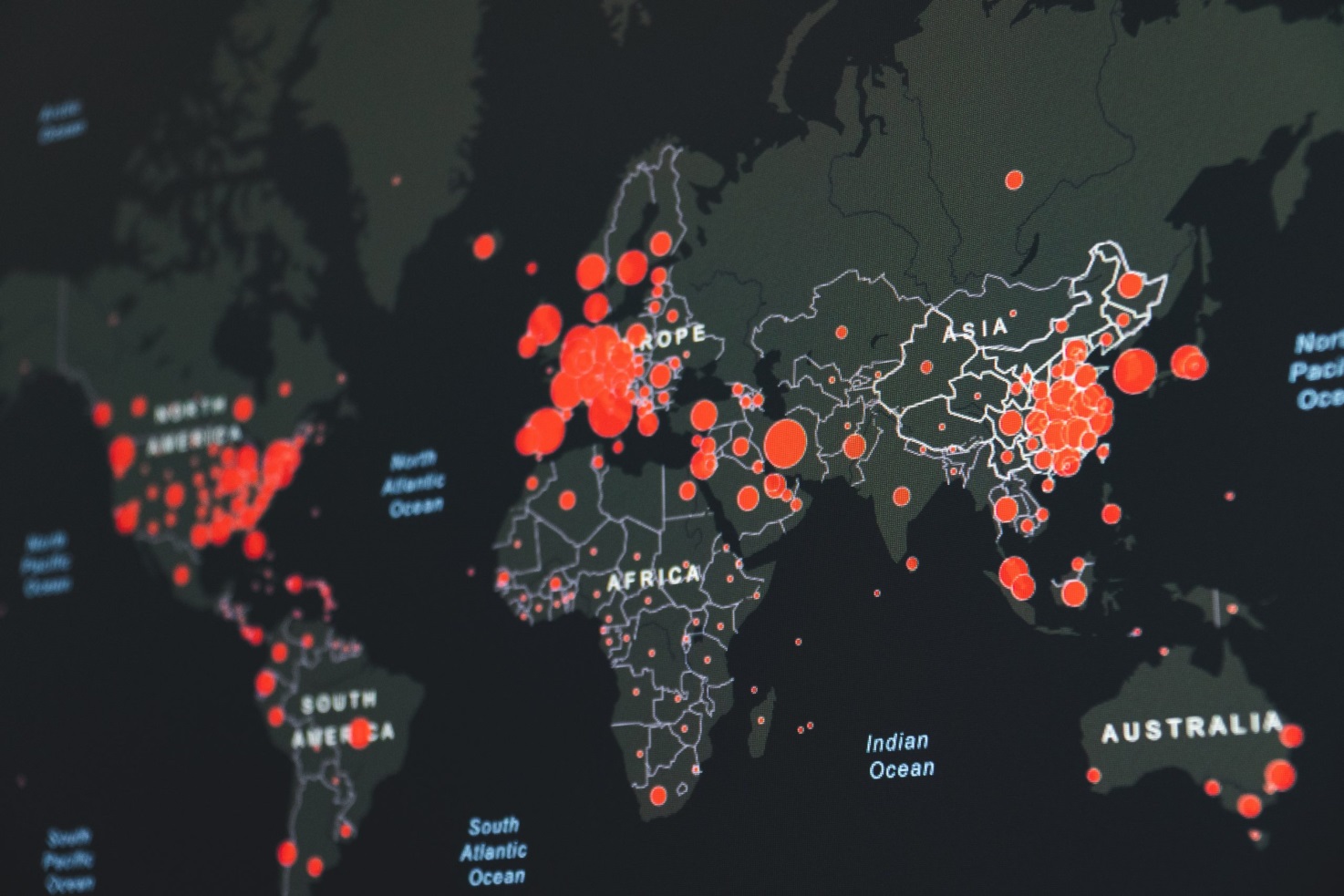

In short, for viruses, the possibilities of coming into contact with a new potential host and quickly reaching every part of the globe had never been so numerous and varied.

RANKING VIRUSES SPILLOVER RISK

But viruses are not all the same. There is an app, called SpillOver, which classifies the most dangerous viruses based on 32 risk factors that could facilitate the transition from animals to humans. The top 12 places in the ranking are occupied by viruses that cause known zoonoses, such as the Ebola virus and SARS-Cov-2. But at lower positions, viruses begin to appear that have not yet jumped into humans, but could in the future. Leading the way are coronaviruses 229E and PREDICT CoV-35, which belong to the same viral family as SARS-CoV-2 and infect bats in Africa and Southeast Asia.

ANIMAL RESRVOIRS

Most of the new virus monitoring studies have focused on bats, which are healthy carriers of a large number of pathogens, including SARS-Cov-2. Recently, researchers identified a new viral strain belonging to the alpha coronavirus genus in bats in Korea. The study of the viral genetic material isolated from the carcasses of 6 bat species showed that the virus renamed HCQD-2020 constitutes a separate strain distantly related to 19 other known alpha coronavirus species. In an article published in Viruses, researchers showed that HCQD-2020 can infect another host, including some species of camels and pigs.

Human alphacoronavirus E229 related strains have been detected in domestic camels, and Alphacoronavirus I species (found in pigs, dogs and cats) have been detected in children with pneumonia in Malaysia. The researchers therefore stressed the need to monitor the new strain and investigate potential new hosts, in addition to bats.

Bats aren't the only animals that cause concern. Animals most studied as potential reservoirs of viruses also include voles (Myodes glareolus), raccoons, dogs, ferrets, minks and other farm animals, such as cows and pigs. Rodents, in particular, are known to be important carriers or reservoirs of numerous zoonotic viruses such as western equine encephalitis, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, Apoi virus disease, haemorrhagic fever of Omsk and the bovine pox of hepatitis E. A review published recently in Viruses explores the zoonotic potential of another coronavirus called Sialodacryoadenitis virus (SDAV), which causes respiratory disease in rats.

THE PAN-CORONAVIRUS VACCINE

All the viruses listed above belong to the coronavirus group. All suggests that a coronavirus might start the "next great pandemic". After COVID-19 vaccines were made in record time thanks to new genetic technologies, the new challenge for world research will be to generate a universal vaccine effective against all coronaviruses. The NIH (National Institute of Health) has already allocated funds for the project "to prepare to face the new generation of coronaviruses with pandemic potential".

In the meantime, however, experts are clamoring for even greater efforts to prevent future pandemics. The fight against the “Next Big Ones”, in other words, can only be said to be truly effective by changing our lifestyles. Eliminate the trade in wild animals, protect areas of the planet with greater biodiversity, apply a tax on the meat trade, finance studies on the monitoring and detection of new infectious pathogens: our success (or failure) against pandemics will depend on this.

Erika Salvatori

Takis, Sars-Cov-2, Covid-eVax, SARS-cov, MERS-cov, David Quammer, Spillover